“A man exists for a generation, but his name lasts to the end of time.”

(The quotations cited in this article are from the Hagakure (“Hidden Leaves”) a book of aphorisms by the samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo, published in 1716, unless otherwise noted).

When you look the artifacts on display at the Cranbrook Institute of Science, remember that each has its own unique story. The practicalities of exhibition design prevent us from relating the saga of all the many wonderful items on display. This is quite aside from the time it would take you to make it through the museum were we to tell them all! So the stories sadly stay untold.

This article tells the story behind several of the artifacts from the Anthropology collection of the Cranbrook Institute of Science. We will begin with a simple description of the artifact and then let our minds range out from there to the history and culture of the people who made and used it. In this way any item, from the grandest piece of jewelry to the humblest of baskets can reveal much of the human condition.

We begin with a real showpiece: a set of Japanese “samurai” armor, made in the 17th century. Frederick Stearns, who co-founded Stearns Brothers’ Pharmacy in Detroit, purchased the armor in the latter part of the 1800’s. He donated it to the Detroit Arts Council (later the Detroit Institute of Arts) as part of a large collection that he had amassed from around the world. It was then passed on to Cranbrook in the 1940’s.

A fearsome, mustached metal visage scowls at you as you approach the armor. This is the menpo (face guard), which protected the wearer’s face and presented a bold facade to the enemy. This hinged guard is attached to the helmet, or kabuto, which includes the bowl, made of thirty-two welded plates, and an articulated neck guard. Like many parts of the armor, this neck guard is made of lacquered steel plates that are tied together with dyed silken cords. A similarly constructed throat guard protected the wearer from deadly slashes to his throat. Odoshi, or armor lacing, was an intricate process, and there was great artistry and variation in the patterns and colors used to create a suit of armor. The sweeping fukigaeshi, or “blowbacks” are richly decorated and feature a mon, or crest, that helps identify the wearer. The whole helmet assemblage is secured to the wearer’s head with a large silken rope tie.

An impressive lacquered and silk-laced breastplate rests below the helmet. This is the ni-mai-do, or two piece breastplate. It is hinged on the wearer’s left side, and is fastened with ties on the wearer’s right. The lacing is done in a style that translates as “sewn spread” referring to the horizontal rows of lacing used to bond the bands of armor together, creating the full piece. Similarly laced pieces of lacquered metal form kusazuri, or waist plates, that hang from the breastplate. This creates a “shell” that provides both mobility and protection. A small cup is mounted at the small of the back, and a bracket is mounted higher up, between the wearer’s shoulder blades. These two attachments held the wearer’s banner, or sashimono, which identified the wearer in battle or on parade.

Sode, or shoulder guards, made in the same manner as the neck and waist guards are attached to sleeves called kote. These have ribbed gourd shaped plates, kyotan gane, and small rectangular plates, ikada, combined with chain mail. The wearer’s thighs are covered by chainmail pieces called haidate, while suneate (shin guards) of leather, mail and metal plates protected the lower legs.

A wooden box, the gusoku bitsu, is used to store the whole assemblage. Shoulder straps on the front allow it to be carried backpack style. It is decorated with two mon, one of which features a torii, or temple gate, with two doves, and is believed to be the family crest, as the armor is credited as belonging to the Torii clan. (This is not a certainty, but for purposes of this article, we will use this family name in our “story”)

Taken as a whole, the outfit represents a pinnacle in the intricate, beautiful craft of Japanese armor construction, an art honed over centuries of incessant warfare. From the seventh century AD up until 1603 when Tokugawa Ieyasu finished the bloody unification of the whole country under his rule as the unchallenged Shogun (military leader), the Islands had known peace only as brief respites between countless wars. Even without any great knowledge of the history and culture of Japan, one cannot help but be amazed at the craftsmanship evident in its construction. But the story this armor can tell you is even more fascinating. To tell the story, we will have to take some “artistic license” and create a fictionalized character, but the life-way of our character and the events that he witnesses are factual.

“Continue to spur a running horse.”

Legends state the first Japanese Emperor, the son of the Sun Goddess Ametesasu Omikami, was crowned in 660 BC; but for centuries the clan had been the basic building block of Japanese society. Large kin groups, clans over time had evolved into political organizations as they vied amongst one another for control of territory. By 300 AD the countless clans had sorted themselves into a hierarchy that unified Japan as a country. For centuries after that clans constantly jockeyed for power and control until Tokugawa Ieyasu’s reign began, marking the start of the Edo period, so named because Ieyasu made Edo (modern Tokyo) his capital. Ieyasu continued the process begun by his predecessor Toyotomi Hideyoshi of making totally solid the long rigid barriers between the military (samurai) class at the top, which was followed by the farmers, then the merchants, then entertainers and other less prestigious occupations. At the very bottom were the eta, or untouchables, people who were tanners, butchers or held other occupations that involved working with dead animals or other activities that were seen as unclean. In Japan, class and clan were one and the same. One was born into a clan of a certain class, and moving up, always very difficult, became neigh impossible during the Edo period, which lasted until 1868. During this period, the Emperor was revered as a glorious symbol, but the Emperor and his family were kept as virtual prisoners in their gilded cage in the Imperial capital city of Kyoto.

Sometime in the 1600’s the armorers of the Torii clan manufactured the armor we see at Cranbrook. Different apprentices trained in forging, lacquering, and lacing worked under the watchful eye of the master armorer. Once the armor was completed, it became the treasured property of one of the high-ranking bushi (warriors) of the Torii clan, which was one of the Daimyo (great names), a ruling family. Ironically, the armor very likely never saw combat. During the Edo period open warfare between great armies was all but unknown. The samurai ruling class had many small uprisings to deal with, and they also were supposed to serve as enforcers of the social order; but such situations seldom called for the wearing of battlefield armor. Instead, this wonderful armor was likely only worn on ceremonial occasions. This likely is how it has come down to us in near perfect condition.

Let us move forward from the time of the armor’s creation to the 1800’s. By now the armor has been handed down within the Torii clan to its current wearer, whom we shall call Torii Tadashi – in Japanese culture the family name precedes the personal name. We will learn a bit about his life and follow him on the day it changed forever.

“A man’s life is a succession of moment after moment.”

Tadashi was born in the family castle, located in one of the provinces. As he was growing up, he would have spent part of his time at home and part of his life living in his family’s estate in Edo. Each local lord was required to live part time at the capital, requiring him to spend a large amount of time and money within the sight of the Shogun. This requirement, along with the fact that some of his family were kept as “guests” of the military ruler, ensured loyalty and kept provincial leaders in check.

This photograph, taken in 1860, shows a samurai wearing a suit of armor of a comparable style to the one discussed in this article.

His childhood schooling began at age seven, learning to read and write under the tutelage of Buddhist instructors. By age twelve, he was learning music, arts, and the skills he would need later in life as the manager of a large estate. At thirteen he underwent a rite of passage called genpuku, where he was given his first adult style haircut, and was presented with his first swords. As a samurai, he was entitled to wear the daisho – both the long sword (katana) and short sword (wakizashi).

Once he became a young adult, Tadashi began his serious training in the arts of war at the clan’s military academy. Back in the days of constant warring, the samurai learned much of their craft from the school of hard knocks by directly participating in battles. The use of the spear and bow were highly valued, as these were the primary weapons on the battlefield. In Tadashi’s time, the use of the sword had become most important, as it was carried with the samurai constantly. Still, Tadashi would have learned from his teachers all three weapons as well as swimming, the basics of horsemanship, and unarmed combat.

Coming from a very wealthy family, he might well have been able to train with specialized teachers of the finer points of swordplay, including iaido, the art of the fast draw. Samurai were bound by a strict code of etiquette called bushido, the “way of the warrior”. Violations of this code often resulted in a duel to the death, even the accidental clash of sword scabbards on the city streets could trigger a deadly exchange. With a lethal encounter only a minor misstep away, the wise samurai learned to draw his weapon and deliver a killing blow all in one smooth motion. As a member of the ruling class, Tadashi could strike dead a member of the lower classes for any reason, or no reason at all, without fear of punishment. Unscrupulous warriors might conduct a “practice murder” or “crossroad cutting” for the grim pleasure of it, in theory without reprisal as commoners were forbidden to carry weapons. In practice, Japanese history is replete with instances where outraged commoners took vengeance upon abusive samurai, individually or as a rebellious group. Still, legally Tadashi held the power of life and death over all those beneath him.

Bushido also governed his own life and death. From childhood members of the samurai class were taught that “the way of the samurai can be found in death”. Absolute loyalty and service to those above oneself in rank defined the samurai’s existence. Death in battle or in service to one’s superior was seen as a desired end. In a like manner, suicide was the honorable alternative to capture in battle. Further, suicide might be chosen by a samurai to atone for his own perceived lapse in behavior or required by one’s superior as a punishment. Such ending of one’s own life could even extend to one’s family, if the extent of one’s transgressions were great enough. Occasionally, a retainer would kill himself in protest against the actions of his superior, suicide being the only form of insubordination allowed. As alien as this fanatical devotion might seem to our modern sensibilities, for Tadashi it was simply the natural way of things. One of the highest placed people in Japanese society, he enjoyed immense power and yet carried stoically great personal and social responsibilities that at any time might require his death. To behave otherwise was to be no better than a barbarian was, and to Tadashi, everyone not born in Japan or China was a little known or understood barbarian.

Japan had long since closed itself off from the rest of the world. Prior to the Edo period Spanish, Dutch and Portuguese traders had visited Japan and established trading posts. When the new military government took over, one of the first actions taken was the expulsion of all foreign influences in Japanese society. The military government expelled all foreign traders and Christian missionaries by 1640. Only one tiny Dutch trading post was allowed to remain, on a tiny man-made island in the bay of the city of Nagasaki. All firearms were confiscated from non-military citizens, and even the military did not utilize them to any great degree. Anyone could shoot a gun with minimal practice.

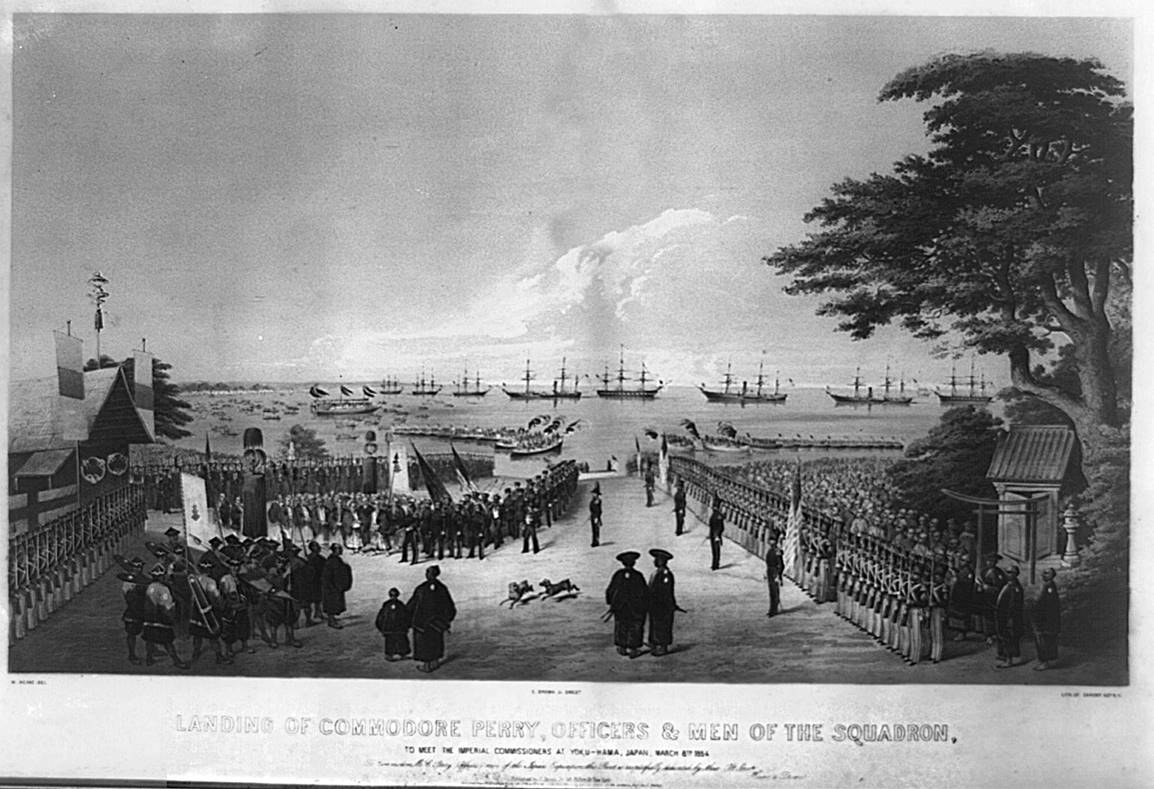

This 19th century work depicts Commodore Perry’s arrival in Tokyo, March 8th, 1854.

By outlawing them, the highly trained samurai made sure that they were the pre-eminent military power. Closed off from the outside world, Japan remained a rigidly self-contained society for many years. Such isolation allowed the ruling class to maintain its firm grip on the country. Tadashi might never have seen a non-Japanese person until July 8th, 1853. On that day, an American fleet of two steam-powered frigates and two sailing ships under the command of Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry made their way into the Edo Harbor. We will follow Tadashi as he watches the beginning of the end of his world.

“Die every morning in your mind, and then you will not fear death.”

While Tadashi may not give much thought to the outside world, the outside world is certainly thinking about Japan. In the United States, President Millard Fillmore is eager to develop American economic and military assets in the Far East. While trade with China is brisk, Japan remains closed off to U.S. ships. In an effort to open Japan, he dispatched Perry to deliver a letter requesting trade and diplomatic relations. Sending the letter with a fleet of four warships was an additional silent, but no less clear, message to the Japanese Emperor. The letter, in part, states “These are the only objects for which I have sent Commodore Perry, with a powerful squadron, to pay a visit to your imperial majesty’s renowned city of Yedo: friendship, commerce, a supply of coal and provisions, and protection for our shipwrecked people.” [Italics added].

Word of Perry’s arrival spreads quickly throughout Edo. Edo is a bustling metropolis of over one million people, living in numerous neighborhoods separated from one another by walls and gates for security and governmental control. Tadashi could see the ships from his great villa located on Kanda Hill in the inland part of the city, known as the Yama-no-te (mountain’s fingers). Kanda Hill had been leveled to provide landfill for the reclaimed lands on the bay, known as the Shitamachi (downtown) area. Many powerful samurai family had then built their estates on the flattened hill, located near the Shogun’s palace. Even before a runner arrived to relay the news about the American arrival, Tadashi realized that this was an unusual event. He barks orders to his servants, commanding them to mobilize his retinue of guards. One servant goes with him to assist him in donning his armor, as this is clearly a time to put on a fearsome show. With his servant’s aid he dons the armor, starting from the bottom and working up, setting the kabuto with its fearsome looking menpo on his head as the final step.

Outside in the courtyard of his estate, his efficient retinue of lower ranking samurai is already formed up, and a groom leads Tadashi’s horse. Tadashi mounts his steed, struggling a bit in his armor, as in truth he seldom has cause to ride in armor. Perhaps one or two of his retinue who come from the provinces might chuckle inwardly at the city-dweller’s lack of equestrian skills; but they would never crack a smile or chuckle, causing immense embarrassment for their commander. With Tadashi mounted, the column quickly gets underway, departing through the front gates of the estate.

Traveling through the length of such a cramped, busy metropolis is no easy feat, any more than traveling by foot the length of Broadway in New York is today. Tadashi’s samurai escort brusquely move aside the citizenry as the entourage travels the through fancy shopping districts, then the great fish market located in a great square next to the Nihonbashi Bridge, which is the official “center” of the great road system of the country. The fish market is jammed with people: fish mongers, porters, cooks, and housewives purchasing the fresh catch from the rich fisheries of Edo Bay. Again, Tadashi’s bodyguard clears a path. In this part of town, perhaps the faces are not quite as friendly as those are among the wealthy in the shopping district. In truth, over the years many in the lower classes have become unhappy with their military rulers. Without wars to fight, many in the samurai class had little to occupy themselves with, other than maintaining their social and economic position through taxation. Naturally, this does not always endear them to the masses. “Shukke, samurai: inu, chikusho!” meaning “Priests and warriors: dogs and animals!” is the quietly murmured sentiment of many.

Amongst the throng in the fish market is a tough looking group of men sporting garish tattoos. These men are members of the local fire department. In a city built largely of wood and rice paper, the risk of fire is an ever-present specter. The fire department is 24,000 strong, split amongst stations at districts around the city. For the most part, hikeshi (firemen) are recruited from the lowest classes due to the dangerous nature of the work. The Edo firemen are intensely loyal to one another. These men are also prone to brawling with rival departments. They affect the hiromono (tattoos) that are based on art prints (ukiyo-e) that illustrate popular stories amongst the common people. These vibrant tattoos became popular amongst many in the building trades as well as the machi yakko (young toughs) who formed street gangs. These gangs see themselves as the protectors of the downtrodden, and revel in brawling and other activities that flout the social order. They are famous for their street battles with the predatory samurai who cause mayhem amongst the common people. The machi yakko form organized crime syndicates modeled after family clans who are often the de facto rulers of their neighborhoods. In such areas even the most powerful samurai normally tread with care.

Tadashi’s group next passes through a large area of the city divided up into smaller districts populated by different tradesmen: weavers, potters, metal workers, etc. In these many districts, entered through gates set in alleyways off the main streets, families involved in the various commercial trades live and work. These busy inhabitants of Edo’s East Side are the Edokko, “children of Edo”. To be a trueEdokko, one has to be born in the city and have the Edo character: hard working, generous, sophisticated in manners, and enormously proud of being a citizen of the greatest city on earth. In short, an attitude that today’s New Yorker would recognize instantly.

Finally, the entourage arrives at the docks where other samurai had arrived, forming an impressive array. In the Bay, the American warships rest at anchor - two of them belching black smoke - all of them bristling with batteries of cannon. Over the course of the afternoon representatives from the city government and the Shogun Ieyoshi Kayama meet with officers from the flotilla. It is a difficult negotiation. Perry insists upon meeting with someone of high rank, and speaks to the Japanese through his officers. On the shore, word spreads that he wishes an audience with the Emperor. Tadashi can not believe that a mere foreigner would have the audacity to meet with the Son of Heaven. Still, the immense power and technology these barbarians possess is obvious for all to see. Tadashi waits on the shore with his fellow samurai, outwardly calm and impassive; but inside, he is in turmoil, wondering what this amazing turn of events might portend…

If only we might fall

Like cherry blossoms in the spring

So pure and radiant

(Haiku composed by a kamikaze pilot during World War II)

After delivering his message Commodore Perry departed for China. He returned in February of 1854 with a fleet of eight ships to receive the reply. The Japanese government chose to agree to a limited open door policy with the Americans, allowing limited trade and re-coaling rights for American ships. With ever-increasing contact with outsiders, the Japanese became aware of both their relative technological backwardness and the weakness of their nation under the Shogunate compared to the barbaric west. Disenchantment with the Shogunate, combined with the impassioned nationalism of the influential scholar Motoori Norinaga and the rising Fukko Shinto religious sect led to the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Under Emperor Meiji, Japan undertook a furious drive towards modernization in order to take its proper place as a world power. The samurai class was stripped of much of its privilege and power was centralized in the hands of a small oligarchy that directed nationalization under the banner of the revered Emperor.

Ironically, the Meiji government harnessed the martial ideology of the samurai as it set out on its quest to make Japan a world power. Japan fought China in 1894 for control of the Korean peninsula, defeating the Chinese and establishing its control over both Korea and Taiwan and forcing China to open three ports for Japanese trade. In 1904 Japan attacked and defeated Russia over the rights to construct a Trans-Siberian railway. In 1910 Japan formally annexed Korea. Emperor Meiji died in 1912, but Japan continued on its course of Imperialism. During World War I Japan participated as a part of the Allied forces; but increasing conflicts with the west over control of South-east Asia led to conflict. Japan took control of Manchuria in 1931 then attacked China in 1937, seizing control of Beijing and Nanking. Japan then turned its efforts towards challenging the United States for control of the Pacific. On December 7th, 1941 Japanese forces launched an attack on Pearl Harbor in an effort to cripple the United States Navy, bringing the United States into World War II.

Unfortunately, modern nationalist sentiment, xenophobia, and military power combined with the unforgiving code of bushido created a military machine capable of great acts of atrocity such as the “Rape of Nanking” where the Japanese Army executed nearly 400,000 Chinese civilians. Although the Japan enjoyed early victories, in the end the United States, the “sleeping giant” that Admiral Yamamoto had warned his countrymen not to awaken, overpowered the Japanese Imperial Forces. Near the end, hundreds of Japanese men became suicide pilots, flying airplanes laden with explosives. Some were literally flying bombs that were released by glider and were then powered by a rocket into American ships. The Americans called them baka (idiot) planes. To the Japanese these pilots were like the “divine winds” that arose to destroy invading Mongol fleets during the 13th century: the Kamikaze.

So ends the story of a suit of armor in the collections of Cranbrook Institute of Science. A story that begins long before it was made, and ends long after. If you would like to know more details of the events that take place in this story of the armor, please refer to the many fine sources used to write this article that are noted below. This author would like to particularly thank Anthony J. Bryant, author of numerous articles and books on the subject of Japanese armor and the samurai warriors, for his personal correspondence during the writing of this article. His work is highly recommended!

References

1994 Bryant, Anthony J., Samurai 1550-1600, Osprey Publishing, Oxford England.

Part of the excellent Osprey Military book series, this volume is a good overview of Japanese armor of the Age of Battles. One of several books in the Osprey line by this author. Mr. Bryant also maintains an excellent website,www.sengokudaimyo.com, with detailed information on Japanese armor, as well as other aspects of Japanese culture of the Edo period and earlier.

1973 Ratti, Oscar & Westbrook, Adele, Secrets of the Samurai, Charles Tuttle Co., Inc., North Clarendon, Vermont.

An in-depth book on the samurai that covers the social organization of the time, the samurai’s physical and mental training, and their arms and equipment. Despite some minor flaws (including listing karate as a martial art of the samurai), an interesting and informative book.

1992 Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Hagakure, Kodansha International, Tokyo, Japan.

This translation is available from amazon.com and should be able to be found at Barnes & Noble or other major book sellers. Translated by William Scott Wilson.

A website devoted to the Japanese art of tatooing, including a great deal of background history of the art and its place in the culture of the Edo period.

http://web.jjay.cuny.edu/~jobrien/reference/ob54.html

President Fillmore’s Letter to the Emperor of Japan is archived here in its entirety, along with a short commentary.

This website includes an overview history of the country of Japan, with a chart of the different periods and the major events of each.

www.compsoc.net/~gemini/simons/historyweb/jeiji-resto.html

A short history of the Meiji Restoration with hyperlinks to related topics, including a short biography of Motoori Norinaga.

Visit this website to take a virtual tour of 19th century Edo (Tokyo), Japan. A wonderful sight with engaging graphics from traditional Japanese prints. Well worth exploring.

A website devoted to Japanese swords. Swords are bought and sold at this site; but there are many wonderful articles on swords located here as well.